It is said that, at 33 years old, Alexander the Great cried salt tears when he realized there were no more worlds to conquer. Over two millennia later, has the chess world found itself in a similar predicament?

After Game 3 in the World Chess Championship, Magnus Carlsen and Ian Nepomniachtchi still find themselves at parity. In fact, when it comes to classical chess, Carlsen has been at parity in the World Championship since the 24th of November 2016 when he beat Sergei Karjakin (in a Ruy Lopez fyi). A whole World Chess Championship against Fabiano Caruana of parity later and we’re still seeing the Ruy Lopez and a Carlsen at parity.

In many respects, Game 3 was inevitable. After the invention and tension of the first two games, the third found itself taking place just before a rest day. Having tested the waters in Games 1 and 2, a more placid draw felt inevitable.

Once again, a Ruy Lopez. Once again, an anti-Marshall line. Once again some novelties, albeit less ground-breaking this time perhaps. Once again some liquidation. And once again, at 40 moves—the first point at which it is possible—a draw.

As always, the wheels of the discourse machine ground into action.

I’ve already talked about the loss of nerve that the purveyors of classical chess have every time there is a draw in the World Championship. The fear seems to be that it is the fact that there can be no winner that is making chess harder and harder to market in the 21st century (rather than, say, the fact that very few admissions are made to make the sport accessible to neophytes in much of the coverage).

But this assumption that a draw signifies a failure of chess needs to be addressed. I would argue that the opposite is the case—it is the draw that makes the World Chess Championship what it is. I’ll try to explain my workings.

The World Championship is a unique moment within the competitive chess calendar. It offers the chance for slow games in long form against two players who have time to prepare. Yesterday’s game was testimony to this fact:

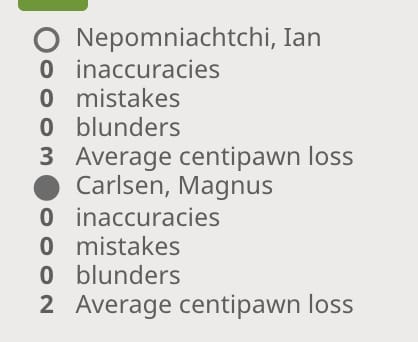

Now, you might look at the Stockfish 14 analysis of the game and argue that, with Carlsen taking the underlying numbers win with a 2-3 centipawn loss, we have reached the end of chess. If we are at a point where the players are performing at the same level as the engines… then what hope do we ever have of seeing wins?

But this misses the point. The World Chess Championship isn’t 14 games in isolation. It is a 14-game match. The three opening draws don’t mean we’re simply back at square one. We have learned something from what went before.

Viewed this way, the draw becomes the baseline result; the given that both players are fighting against. What we are looking for is for players to avoid the inevitable; outsmart their opponent and then, having outsmarted them, force the advantage.

There is a repetitive beauty to these Championship games where the players take a line and probe it. Game 1 - Nepomniachtchi with white: try the h3 anti-Marshall line. Game 3 - Nepomniachtchi with white: try the a4 anti-Marshall line. Game 5 - Nepomniachtchi with white: try the d3 anti-Marshall line?

The draws are not failure then but the background against which the World Chess Championship comes into sharper relief. They offer the context within which the match has meaning. There is a cumulative element to them. You cannot simply look at them in isolation and declare them a “short draw - uninteresting”. They acquire meaning against the other results in the match.

Of course, arguments can be made that the draw has become too much of a given. That a player can hold onto draws and make their way through to a more conducive rapid format if they fancy their chances there. Solutions to this problem will certainly need to be discussed by FIDE (and my own hunch is that time controls could be the solution here).

But let’s not forget what it is that makes the World Chess Championships so unique in the competitive chess calendar. It’s slow play. Long form. Against two players who have time to prep. This is the chance to see just how well the game can be played without any of the usual limitations that we place upon the sport. That we end up with a lot of draws is merely testament to how high the standard is.

Have we reached the end of chess? The temptation always is to think that our generation is unique. But there is always another generation waiting in the wings to take its place. Alireza Firouzja has just waltzed his way up the world rankings after beating everybody in the European teams in Slovenia. I’d say we’ve still got plenty of future to go yet.