Long Live the Beautiful Game

Game 11 ended a disappointing World Chess Championship. But should we write off this tournament's place amongst the Pantheon?

Beneath the story of a love couple, Titanic tells another story, the story of a spoiled high-society girl in an identity-crisis: she is confused, doesn't know what to do with herself, and, much more than her love partner, di Caprio is a kind of "vanishing mediator" whose function is to restore her sense of identity and purpose in life, her self-image (quite literally, also: he draws her image); once his job is done, he can disappear. This is why his last words, before he disappears in freezing North Atlantic, are not the words of a departing lover's, but, rather, the last message of a preacher, telling her how to lead her life, to be honest and faithful to herself, etc.

Slavoj Žižek, A Pervert’s Guide to the Family

As the confetti blows away and the crowds disperse, as the venue for the World Chess Championship is dismantled, as the media pack away their equipment and file their final reports, there occurs an unobtrusive shift from present to past. From this point on, there can be no new content added to the World Chess Championship 2021. There is nothing left but for it to enter the canon.

But there is no saying what form this canonisation will take. On the face of it, the World Chess Championship 2021 was one of the most disappointing iterations of a competition that has an illustrious heritage.

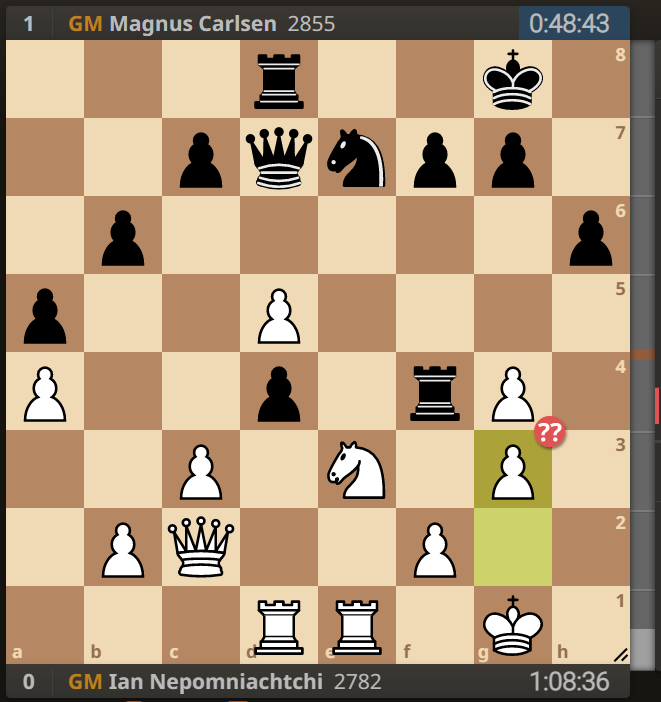

The match ended in a manner befitting the post-Game 6 proceedings; Ian Nepomniachtchi seemingly intent on simply having a blunderful Christmastime. In many respects, Game 11’s blunder is chastening to amateur chess fans (amongst which I include myself, I hasten to add). The game was pootling along nicely with the engines thrumming out a line of zeros in the position. But then, 23. g3??

At this point, Stockfish 14 lurches downwards to -6.6. A simple pawn push and then death to the position. What an awful game chess is.

From this point onward, Carlsen was in the driving seat. A liquidation followed and before anyone knew it, the Norwegian was in a rook endgame with a pawn up. A promoted pawn later and there was nothing for it. Nepomniachtchi resigned. Carlsen retained his title.

The temptation here is to write off the match. No doubt it will be brushed aside in future retellings of World Chess Championship history as “that match where Ian Nepomniachtchi collapsed.” But is it quite as simple as this?

The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek is a lot of things. But one of his more admirable qualities is his ability to retell stories in interesting ways. His retelling of the film Titanic, sees him read the iceberg as the hero of the film. On the face of it, the story seems to be a Romeo-and-Juliet-type love story that is ruined by the vicissitudes of history. Žižek sees it differently:

[O]n the deck, Kate [Winslet] passionately says to her lover that, when the ship will reach New York the next morning, she will leave with him, preferring poor life with her true love to the false corrupted life among the rich; at THIS moment the ship hits the ice-berg, in order to PREVENT what would undoubtedly have been the TRUE catastrophe, namely the couple's life in New York - one can safely guess that soon, the misery of everyday life would destroy their love.

As a result of this re-reading of the film, Žižek is able to describe Leonardo di Caprio’s character, Jack, as a “vanishing mediator”—an agent fundamental to Rose’s transformation who must disappear in order for this transformation to be complete. Were he not to disappear, then the transformation might unravel as Rose begins to resent Jack for the stark reality of a life of poverty.

Make of that what you will. But it makes me wonder if Ian Nepomniachtchi will function as something of a vanishing mediator in the canon of the World Chess Championship.

In labeling a World Championship match “disappointing”, the inference seems to be that every World Championship match should live up to an ideal. We expect every edition of the competition to involve scintillating chess; chess that is worthy of the highest level of the sport.

Now, I am no chess historian but I know that this has never been the case. This failure of chess to produce has even been played out in this World Championship match. For the first six games of 11 eventual games, the chess was of remarkably high quality. After Game 6, a seismic shift occurred.

This is how it goes. There is an argument to be made that the bad chess is a necessary condition for the good chess. The good chess comes into stark contrast against the background of the bad chess. Aesthetically, you might like the bad chess to proceed the good chess (as it did, for example, in the first iteration of the Karpov-Kasparov matchups) but you can’t have everything. In this sense, then, the Carlsen-Nepomniachtchi match, despite its vanishing qualities as a spectacle, will become fundamental to the context of future World Championship matches.

But that’s not to make a banal point. It’s not just to say “well here’s some bad chess to make you look forward to good chess next time around”. There is an emotive element here too. The road to the top of the chess pyramid is a hard one. You can find the form of you life, make it through the arduous Canditates process, amaze the world with your impressive preparation for six games and then find yourself out on your arse, spat out of the World Chess Championship at the other side.

This is chess. This is what it does to us. The success of Magnus Carlsen is augmented against the backdrop of what the game has done for Ian Nepomniachtchi. And what it does to us in our own dabblings amongst the pieces.

Ian Nepomniactchi finds himself a vanishing mediator, then. A necessary agent in the ever-evolving history of the World Chess Championship. Moving us onto the next match in our continued search for good chess. But simultaneously reminding us of what’s at stake as the match is promptly forgotten.

This is chess. Long live the beautiful game.